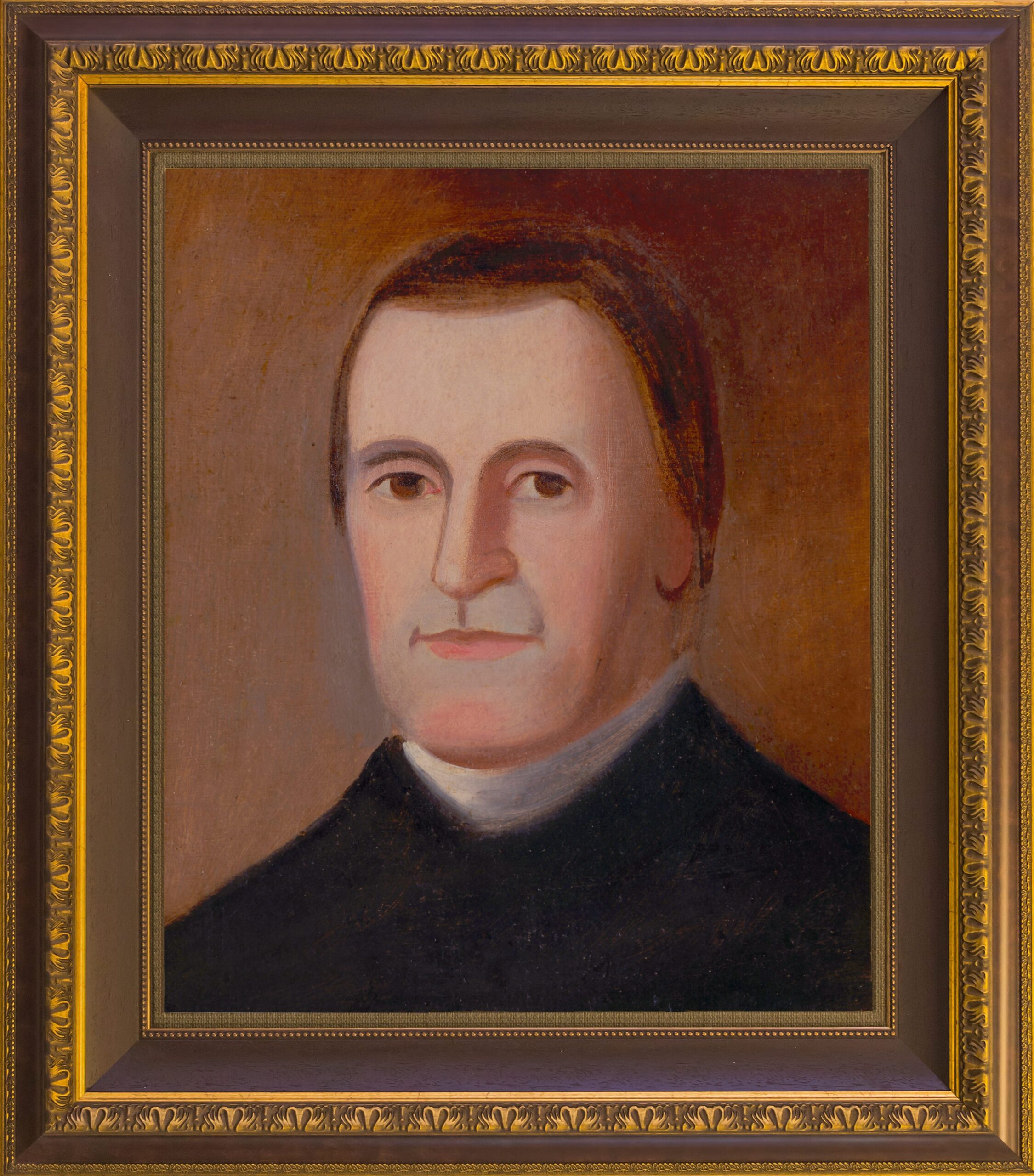

Title: Portraits of signers of the Declaration of Independence

Call Number: MSS 12130

Citation: Robert Edge Pine. Copies of Pine's Portraits of Signers of the Declaration of Independence,1820, Accession #12130, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

This photo has been identified as being free of known restrictions under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights.

Spouse Information:

Elizabeth Hartwell

(1726 - 1760)

Mehetabel Wellington

(1687 - 1776)

Children:

7 children - John, William, Isaac, Chloe, Oliver, a second Chloe and Elizabeth. The first Chloe, Oliver and Elizabeth died in infancy.Roger Sherman

“My friend, you should fit yourself to be a lawyer.” The tall, awkward young man to whom these words were addressed looked surprised. “I! Why should I be a lawyer?” he asked. “Because you have drawn these notes so that, with a few alterations in form, they are as good as any petition I could have prepared myself; no other one.

Such was the statement of a leading attorney of New Haven, Connecticut sometime in the 1740’s, to Roger Sherman, a young surveyor of New Milford in the same colony. He had been commissioned by a neighbor to consult a lawyer about a matter demanding a petition before a legal court. He had thought it well to set down as best he could the various items of the plea. When the lawyer asked to see his memorandum he surrendered it rather reluctantly-it was merely a memorandum of his own, he said, and feared it would be of little service. Then followed the opening conversation noted above.

Roger Sherman felt it was not then possible to follow the lawyer’s advice, for he had assumed a considerable share of the support of his widowed mother and his four younger brothers and sisters. His work as a surveyor was proving profitable and he felt he must devote himself altogether to it, but he studied law in his leisure moments, and some years later was admitted to the Connecticut bar.

Ancestry

The name Sherman was not uncommon in England as long ago as the fourteenth century. Roger Sherman’s family has been traced with a great degree of probable accuracy to a certain Thomas Sherman of the little town of Diss in southern Norfolk, England. The family-owned lands in nearby Yaxlee in Suffolk county and later in Dedham in Essex on the River Stour. At Dedham Henry Sherman served apprentice to a shearman, or maker of woolen cloth from the sheared wool, from which his family name was doubtless derived.

Several generations later, John Sherman, the first of Roger Sherman’s ancestors to settle in America, immigrated to New England about 1636. The following year John Sherman married Martha Palmer and they settled in Watertown, MA. Watertown was the home of three further generations of the Sherman family headed by Joseph, William and our subject, Roger. Different branches of the Sherman family have yielded many men of prominence in the later history of our country. John Sherman’s cousin Edmund of Dedham, Essex immigrated to America and was living in Wethersfield, CT in 1635. From John came his son Samuel, who spent most of his life as a prominent layman in church and state in New Haven Colony. From Samuel were descended General William Tecumseh Sherman and his brother, Senator, and Secretary of State John Sherman.

Returning to William Sherman, son of Joseph, he seems to have had the spirit of wanderlust. As a younger son, he turned from his ancestral home in Watertown, MA and sought his daily bread in Charlestown, then Newton and finally in Stoughton, all near present-day Boston. After the death of his first wife and child he married Mehetabel Wellington, daughter of Benjamin Wellington and granddaughter of Roger Wellington, a planter and substantial landowner of Watertown. From Roger Wellington, Roger Sherman received his name.

Childhood

Seven children were born to William and Mehetabel Sherman: William Jr., Mehetabel, Roger (April 19, 1721), Elizabeth, Nathaniel, Josiah, and Rebecca. At about the time of Elizabeth’s birth (1723), the Shermans left Newton and settled in the south precinct of Dorchester, which three years later became the township of Stoughton, MA.

Newton could claim Roger Sherman as a resident for only two years of babyhood. The family purchased a tract of land on the highroad near Stoughton, now Pleasant Street. It must have been a somber childhood with few material comforts and little play or entertainment. Freezing bedrooms and icy pitchers were common and as he grew, Roger learned to plow a furrow and cut cordwood. These were the years in which he developed an iron constitution, unflagging industry, and unconquerable courage. His father William Sherman was a small-town farmer, and to supplement his income during the intervals in farming he chose the trade of cordwainer (from cordwain, cordovan leather), or shoemaker or cobbler. Roger must have learned this trade from him.

The Sabbath began at sunset on Saturday and was cheerlessly observed during the better part of the day at the meetinghouse on Sunday; for children, both work and play were banned. Sunset must have brought a guilty sense of relief! Nevertheless, the experience instilled in Roger an unbending set of Christian values that were to serve him well throughout his life, values that are unfortunately not visible in many of our leaders in the twenty-first century. School facilities had deteriorated from the standards cherished by Bradford and Winthrop. The elementary school had disappeared altogether in many towns. Educational standards were, however, improving and the first schoolhouse was erected in Stoughton in 1734 near the present Canton Corner. Quite probably, Roger Sherman was among its first pupils, trudging daily nearly a mile from home to school.

Reading and writing were taught but this did not imply excellence or uniformity in spelling. Grammar must have been in the curriculum. President Dwight of Yale said of Sherman after he had attained prominence, that he was “accurately skilled in the grammar of his own language.” The Stoughton school required their teachers to be “sound in the faith” and that they catechize the scholars in the principles of Christian living. Town schools met only in the winter; for the rest of the year, Roger worked on the farm or at shoemaking.

Arithmetic was doubtless taught at Stoughton, but if the instruction did not extend beyond long division, Roger must have learned by other means. His expertise is evidenced by the complex mathematical calculations used to prepare astronomical tables in his published almanacs. In any case, we know that he had acquired at an early period far more education than he could have gained from the village school.

Early Career and Marriage

In 1740, William, Roger’s older brother, now twenty-three, took up residence in New Milford, CT, about 160 miles southwest of Stoughton near the western border of Connecticut. Roger was soon to follow. In March 1741 William Sherman the father died, leaving no will. The probate court assigned William’s real estate of 109 acres to Roger, then only nineteen years old, obligating him pay to his mother and siblings the appraised value of the share to which each was entitled. This was an unfair arrangement for Roger, as he was able to sell the real estate for little more than one-fourth its appraised value, and was consequently burdened with debt. Nevertheless, from this time he assumed the support of his mother and the younger members of the family, and in a few years seems to have made full settlement.

Roger Sherman, with his mother and younger siblings soon moved to New Milford where he continued his farming and cobbler work. It is a mistake, however, to classify Roger Sherman as a shoemaker. While honorable and necessary work, it holds scant opportunities for exerting great influence, and it was Roger Sherman’s calling only long enough to fit himself for a better one. (A great-great-grandson of Roger Sherman reported that his grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Roger Sherman, Jr., laughed at the stories of the Hon. Roger’s shoemaking and said he never made a pair of shoes in his life (he was a surveyor at age 24)). He pursued his mathematical studies and in 1745 was appointed by the General Assembly of Connecticut as the Surveyor of Lands for the county of New Haven.

Sherman frequently revisited his old home in Stoughton, MA. One reason for this attraction is revealed when we discover that during one such visit, on November 17, 1749, he was united in marriage with Elizabeth Hartwell, eldest daughter of Deacon Joseph and Mary (Tolman) Hartwell of Stoughton. Seven children were born to Roger and Elizabeth in New Milford: John, William, Isaac, Chloe, Oliver, a second Chloe and Elizabeth. The first Chloe, Oliver and Elizabeth died in infancy.

Almanacs

Over the next eleven years Roger Sherman devoted himself to the issuing of a series of almanacs. In the Boston edition of his first almanac (for 1750) we find this announcement:

“To the READER I Have for several Years past for my own Amusement spent some of my leisure Hours in the Study of Mathematicks; not with any Intent to appear in publick: But at the Desire of many of my Friends and Acquaintance, I have been induced to calculate and publish the following ALMANAC for the Year1750-I have put in every Thing that I thought would be useful that could be contained in such contracted Limits:-I have taken much Care to perform the Calculations truly, not having the Help of any Ephemeris: And I would desire the Reader not to condemn it if it should in some Things differ from other Authors, until Observations have determined which is in the wrong.-I need say nothing by way of Explanation of the following pages, they being placed in the same Order that has been for many Years practised by the ingenious and celebrated Dr. Ames, with which you are well acquainted.-If this shall find Acceptance perhaps it may encourage me to serve my Country this Way for Time to come.

New Milford August 1, 1749.”

This activity is significant in that in those days the almanac largely supplied the place of the newspaper. “Except the Bible,” we are told, “probably no book was held in greater esteem or was more widely read in the colonies in the eighteenth century than the almanac.”

Merchant and Lawyer

Also, in 1750 William Sherman had purchased the site of the present New Milford town hall and the brothers had established a general store there. Roger had a half-ownership in the shop although William had the leading role in its activities. Roger found his merchandising and surveying businesses lucrative, and as his circumstances became easier, he invested extensively in land. In 1756 his property ranked seventeenth in value among New Milford property holders. He studied such legal works as he could find with as much zeal as he had formerly studied mathematics and surveying, and friends, and acquaintances soon sought legal assistance through his counsel. He applied for admission to the bar and was granted the right to practice in the Litchfield County, CT courts in February 1754. By 1755 he had 125 cases in the Litchfield and Fairfield County courts and was fairly launched as a successful lawyer.

It is abundantly evident that in the New Milford years Roger Sherman had plenty of irons in the fire. Remarkable ability and energy were required to conduct a busy career as a surveyor, calculate and issue an annual almanac, devote time, and thought to a merchandising enterprise and embark on an expanding career as a lawyer. But this is not the whole story. As a man prospers and proves his capacity and character, his townsmen ever turn to him for assistance and advice in public matters. Accordingly, we find that both in church and in civic life Sherman was soon filling positions of trust. He appears in October 1754 as a New Milford selectman and in the following year as a justice of the peace for Litchfield County as well as election to the General Assembly of Connecticut. He was re-elected semi-annually until he left New Milford in 1761. During these New Milford years Sherman also served his church in several significant offices and committees, including a 1752 appointment as Treasurer of the church Building Fund.

In October 1760, Roger Sherman’s wife Elizabeth died at the early age of thirty-four. This loss may have been one of the motives for his leaving the small town of New Milford. He may well have reasoned also that there would be a wider field for his talents in one of Connecticut’s large cities. He chose New Haven, the site of Yale College and sharer, with Hartford, of the seat of government.

Start of Political Career and Second Marriage

By the fall of 1764 Sherman was elected as deputy from New Haven to the colonial Assembly, and was re-elected for the two sessions of 1765 and the spring session of 1766. From 1760 onward he was among the twenty citizens that every town had the privilege of nominating for the posts of governor, deputy governor, twelve assistants (members of the upper house of the colonial General Assembly), secretary and treasurer. In 1765 he was chosen as justice of the peace for New Haven County and as justice of the county quorum, in 1766 an assistant, and in May 1766 as judge of the Superior Court of Connecticut.

In New Haven Sherman occupied a house adjoining his store, purchased the preceding year. The property consisted of well over an acre opposite the Yale College grounds. He devoted himself to the sale of general merchandise, including books, in which occupation he was very successful. He continued to operate this store until 1772, when he turned it over to his son William and devoted himself wholly to public life. Though he himself was denied any extended schooling, Roger Sherman assisted his brothers to secure a higher education. Now, Yale College, in its turn appreciating Sherman’s interest, integrity and abilities, elected him as its treasurer in 1765. Around 1768 he built a new house on Chapel Street that was his home for the remainder of his life. He was already recognized as one of New Haven’s substantial citizens.

During a trip to Stoughton, MA to visit his brother Josiah, Sherman declined an invitation to stay longer, citing urgent business matters in New Haven. On their way to Woburn, as Roger and Josiah paused before going their separate ways, they met Miss Rebecca Prescott, twenty, who was in Stoughton to see her Aunt Martha, Josiah’s wife. Roger, then forty-one, quickly decided that his business commitments were not as urgent as he had thought, and extended his visit.

Roger and Rebecca were married on May 12, 1763 by her grandfather, the Reverend Benjamin Prescott. Rebecca’s father, Benjamin Prescott, a magistrate and prosperous merchant in Salem, MA, and her grandfather of the same name, were both graduates of Harvard College. The Prescotts’ ancestry has been traced, with probability, to Alfred the Great. Rebecca Prescott was, by all accounts, a charming and lovely woman of high character, blessed with an alert and ready wit and much practical ability, well fitted to supplement Roger’s shrewd common sense by her womanly insight and counsel. A new family was born to Roger and Rebecca: Rebecca, Elizabeth, Roger, two Mehetabels, Oliver, Martha, and Sarah. All lived to maturity except the first Mehetabel, who died in infancy.

Colonial Unrest

The American colonies were, in general, grateful to Great Britain for its role in protecting them from French dominion during the French and Indian War. Better, freer times were surely ahead. But the war had left Britain with a staggering debt. It was reasoned that a military establishment must be maintained and that the colonies should provide a large part of the cost through a British tax on sugar or molasses, America’s commercial lifeblood, as well as on other imports. A proposed Stamp Act required that many printed materials in the colonies carry a tax stamp. The colonists saw no need of troops; there was no longer a French menace, and they could take care of the Indians by themselves. From Britain’s standpoint, that the colonies should not wish to contribute their fair share was simply not playing the game.

Parliament passed the Stamp Act March 22, 1765, to take effect in November. The Massachusetts Assembly proposed a congress of the colonies, to be held in New York in October, to protest the Stamp Act, and Roger Sherman was one of the deputies appointed to represent Connecticut. This congress “was the first unmistakable evidence that the colonies would make common cause.” Petitions to the Crown and Parliament were drawn up asserting the colonies’ rights of levying their own taxes and of trial by jury; the Stamp Act was condemned, but no threats were uttered. It was resolved that no business requiring stamped paper should be transacted in the colonies that winter. On November 1, New Haven’s bells were all tolling; the churches proclaimed it a day of fasting; no civil courts sat; real estate transactions ceased to be recorded.

The radical element, the “Sons of Liberty,” took control of much of the New England colonies and Connecticut’s governor was unable to subdue them. Sherman’s view of these high-handed doings reflected the feelings of the law-abiding citizens. “I have no doubt of the upright intentions of those gentlemen who have promoted the late meetings in several parts of the Colony which I suppose were principally intended to prevent introduction of the Stamp papers, and not in the least to oppose the laws or authority of the government; but is there no danger of proceeding too far in such measures?”

Commercial interests in London as well as English workingmen were feeling the pinch of the Stamp Act; the repeal bill was passed by Parliament and signed by the King on March 18, 1766. However, a combination of ineptitude and malice on the part of the British government continued to whittle away at the liberty of the colonists. The continuing tax on tea provoked the “Boston Tea Party,” the Crown replied with the five “intolerable acts,” and open hostilities became inevitable.

The Articles of Association

In May 1774, the Virginia Burgesses had proposed a congress of all the colonies. Massachusetts proposed that they meet in September at Philadelphia. The other colonies, save for Georgia, acted on this suggestion and the First Continental Congress was launched. The Connecticut delegation consisted of Eliphalet Dyer, Silas Deane, and Roger Sherman. Deane’s renown, and Dyer’s as well, have largely faded. When the outstanding men of the First Continental Congress are named today, it is Sherman (though chosen last of the three) who is mentioned as representing Connecticut; Woodrow Wilson remarks: “Connecticut’s chief spokesman was Roger Sherman, rough as a peasant without, but in counsel very like a statesman, and in all things a hard-headed man of affairs.”

The two great accomplishments of the Congress were a petition to the King, and an agreement among the delegates, called the “Articles of Association,” to wholly abstain from importing, buying, or using any goods from Great Britain, and from exporting any American products to England or the West Indies until the objectionable law was repealed by Parliament. This “memorable league of the continent in 1774, which first expressed the sovereign will of a free nation in America,” to use words attributed to John Adams, was the first of four great documents of our early history signed by Roger Sherman. He alone signed all four. The others were, of course, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. Shortly after their return to Connecticut in November 1774, the Connecticut Assembly reappointed its three delegates to represent the colony in the Second Congress the following May.

Prolog to War

Conditions in Massachusetts and Connecticut deteriorated quickly. General Gage’s April expedition to Lexington and Concord produced serious consequences, prompting Connecticut’s Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen to proceed to and seize England’s Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point. On the same day, May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress met at Philadelphia. With hostilities already begun, the assembled delegates found plenty of subjects to occupy their time. Undoubtedly, the Congress’s most important action was the adoption of the troops around Boston into a Continental Army, and the appointment, at the urging of John Adams, of Virginian George Washington as its commander. Roger Sherman initially opposed this appointment, preferring a New Englander, but when the question came to a formal vote, he gave his vote with the other delegates in making Washington’s election unanimous.

The story of the weary months of inaction in 1775 and early 1776, while Washington wrestled with lack of munitions and equipment, profiteering, lack of discipline and wholesale troop desertions is familiar. Washington sought an efficient military by having soldiers enlisted for the period of the war, but Congress would not consent. Opposition to a standing army had long been the watchword of liberty, and Roger Sherman was one of those who supported this view. On November 1, 1775 Congress learned that King George had not only refused to receive their earlier petition, but had issued a proclamation that the colonies were involved in a rebellion which must be put down with the sword. Hope for reconciliation was ended.

In October, the Connecticut Assembly had chosen Roger Sherman to remain in Philadelphia as its representative, along with two new delegates. Unprovoked attacks on defenseless seaports, rumors of the hiring of German mercenaries to subdue them, and other acts of British hostility made a Declaration of Independence inevitable. A young Englishman recently arrived in America, Thomas Paine, produced a pamphlet, Common Sense. Twenty thousand copies sold in three months, converting multitudes to the idea of independence. When Congress considered opening America’s ports to foreign trade, Sherman observed “We cannot carry on a beneficial trade as our enemies will take our ships …a treaty with a foreign power is necessary before we open our trade, to protect it.” By June, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland had joined Georgia, the Carolinas, Rhode Island and Virginia in endorsing Richard Henry Lee’s resolution that the colonies “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.”

The Declaration of Independence

On June 11, a committee was appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence “Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. Livingston, representing New York, seems to have doubted whether the time for action had yet come. His absence from Philadelphia prevented his signing the Declaration as adopted. Jefferson prepared the paper, submitted it to Adams and Franklin where a few minor changes were made, and then to the whole committee where it was unanimously approved. The Declaration was presented to Congress on June 28. Certain changes were made while the document was under discussion, notably the elimination of the passage condemning the slave trade.

John Trumbull’s well-known painting, often mistakenly called the “Signing of the Declaration of Independence,” shows only the presentation of the draft. It now hangs in the United States Capitol Rotunda and is the source of the figure on the two-dollar bill. The five figures standing before the table, left-to-right from the viewer’s perspective, are: John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin.

On July 2 the Lee resolution was adopted by a vote of 12 to 0, New York alone not voting. On the evening of July 4, by the same vote, the Continental Congress, representing the United States of America, adopted, and thereby proclaimed to the world its Declaration of Independence. The great paper was referred to the committee for redrafting in its final form; this was done that very evening. Copies were printed July 5 and, over the signatures of John Hancock, president of Congress and Charles Thomson, secretary, were sent to governors of States and to General Washington and other commanders. On July 8 the Declaration was publicly read in Philadelphia amid the cheers of the listeners. Soon afterward the New York delegates received instructions to give it their support. Later it was signed by delegates from all the colonies. The new nation was born.

War and the Articles of Confederation

The months following the Declaration were discouraging. The battle of Long Island, the evacuation of New York and the retreat across New Jersey strengthened the opinion that the Declaration consisted of brave words that could not be carried out. New Haven was divided between conservatives and radicals; Tory influence began to be felt and lukewarm patriots lost courage. Yale College was disbanded for a time. By 1778, however, news of the success at Saratoga brought acclaim to General Benedict Arnold and raised patriot spirits.

Roger Sherman’s time and thoughts were consumed with the government of the new republic. On the very day following his appointment to the committee to frame the Declaration of Independence (June 12, 1776), he was placed as Connecticut’s representative on a committee of thirteen (one from each colony) to draw up Articles of Confederation. A draft was reported in July 1776 but the Articles were not adopted in final form until November 1777. Sherman suggested a plan of representation with an upper branch with one vote per State and a lower branch with votes apportioned according to the number of each State’s free inhabitants. This plan was not incorporated in the Articles of Confederation, but was later secured for the Constitution in 1787. After adoption by Congress the Articles had to be approved by every State, a very difficult requirement. After much agonizing on the part of the States, Maryland was the last to ratify the Articles, and a genuine confederated government, with whatever deficiencies, was finally in place.

Roger Sherman was chosen as delegate from Connecticut to the Continental Congress each succeeding year throughout the Revolutionary War until 1781. He was not chosen that year but was appointed later to fill out the term of Titus Hosmer, deceased. Congress had no authority whatever to enforce its recommendations except such as the States gave it, and the thirteen states could seldom agree on anything. They allowed inefficiency. There was a failure of the delegates to trust and support Washington, their chosen commander. Congress was weak because the States, fighting to free themselves from England, were loath to substitute for that regime a super state in America. Sometimes only one delegate, or none, was on hand to serve a State. Personnel changes weakened Congress; neither in character nor in ability did the later membership average as high as in the days of ’76. Connecticut’s delegates however, were strong and able men throughout the Revolutionary period.

Service in the Continental Congress

Roger Sherman was assigned to several important posts at every congressional session, and worked continuously, to the detriment of his health and strength. On the Board of War, he made visits to the front and attended prolonged conferences with Washington and others. He served every year on one or more committees dealing with finance, purchasing supplies (he even surprised his colleagues with his knowledge of the shoe industry) and later the Board of Treasury. “A single brilliant exploit in the field, a single eloquent sentence on some dramatic occasion, would doubtless have done more to keep alive the memory of a man like Ellsworth or his colleague Sherman, than all the patience, judgment, energy and devotion with which, through many weary weeks and months, they gave themselves to the things which no one wished to do, yet which must be done, and could only be done by men of first-rate ability.” “He was noted and esteemed” says one of Connecticut’s historians, “for his calmness of nature and evenness of disposition. His rationality was his distinguishing trait: common-sense in him rose almost to genius.”

We know that the outcome of the American Revolution was due to, more than any other factor, the indomitable courage, persistence, and resourcefulness of George Washington. But there were other important factors, not the least of which was the morale diffused throughout the country by leaders like Roger Sherman, who, refusing to admit defeat, threw their whole moral force into the cause of their country. The greatest factor was the invincible urge of human freedom!

And so, at length came Yorktown and the surrender of Cornwallis. The joyful news was announced to Governor Trumbull in a letter signed by Roger Sherman and his fellow Connecticut delegate Richard Law:

Sir, we have the honor now to transmit to your Excellency an official account of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis and the army under his command. The dispatches from General Washington were received yesterday morning…This great event, we hope, will prove a happy presage to a complete reduction of the British forces in these States, and prepare the way for the establishment of an honorable peace.”

The Constitutional Convention

The final years of the war had brought great financial distress to Sherman. Nevertheless, by1784 he was holding four civil offices: he was on the Governor’s Council and the Connecticut Superior Court, he was in the Continental Congress and he was mayor of New Haven. (At word of his mayoral election, his seven-year-old son Oliver is said to have asked “who is to ride the mare?”) “His person was tall, unusually erect, and well proportioned, and his countenance agreeable and manly. His abilities were remarkable, not brilliant, but solid, penetrating, and capable of deep and long investigation. In such investigation he was greatly assisted by his patient and unremitting application and perseverance.

Monetary inflation, brought on by demands of the debtor class to issue more and more paper money, and highlighted by the well-known Shay’s Rebellion in Massachusetts, roused men in all the States to a realization of the nation’s dangerous condition. Since 1782 a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation had often been proposed. The Articles were admirable up to a point; nothing better of their kind had ever been produced. They allowed the States ample freedom and allocated appropriate, though inadequate, powers to the Federal Government. They failed in not clothing the Federal Government with enough power to compel what was absolutely needed for its own maintenance and effective functioning.

After several false starts Congress invited each State to appoint delegates to a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation. Every State except Rhode Island responded and the Constitutional Convention assembled at Philadelphia in May 1787. Roger Sherman represented Connecticut along with William Samuel Johnson and Oliver Ellsworth. John Adams wrote in 1822: “It is praise enough to say, that the late Chief Justice Ellsworth told me that he had made Mr. Sherman his model in his youth. Indeed, I never knew two men more alike, except that the Chief Justice had the advantage of a liberal education, and somewhat more extensive reading.” On the other hand, a future Congressional colleague, Jeremiah Wadsworth, warned Rufus King that he was satisfied with the Connecticut delegation “… except Sherman, who, I am told, is disposed to patch up the old scheme of government. This was not my opinion of him, when we chose him: he is cunning as the Devil, and if you attack him, you ought to know him well; he is not easily managed, but if he suspects you are trying to take him in, you may as well catch an Eel by the tail.”

It must be noted that the Convention was not a thoroughly democratic assembly; it represented the conservative classes who had been chosen in every case by the State legislatures; there were no small farmers or mechanics among them. Sherman was one of the most frequent speakers on the floor of the convention, his 138 speeches surpassed only by Gouverneur Morris, James Wilson, and James Madison. The delegates, notably those from Virginia, favored a completely new system rather than an amended Articles of Confederation. Although agreeing on many of the proposed provisions, the smaller States stoutly opposed the larger States on the question of representation. The small States felt that the dignity of each State demanded its equal representation with the largest. The large States wanted representation based on their population of free men. On June 11 however, Roger Sherman proposed “that the proportion of suffrage in the first branch should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more.” The motion was voted down 6-5.

After much more acrimonious debate the Convention seemed to have reached an impasse. A committee of one from each State was appointed, and on July 5 it reported that representation in the lower house should be one member for each 40,000 population. In the upper house each state should have an equal vote. The Convention adopted this report. The “Connecticut Compromise” had triumphed. After further debate the new Constitution was completed and signed by forty-one delegates on September 17. We learn from Washington’s Diary, “The business being thus closed, the members adjourned to the City Tavern, dined together, and took a cordial leave of each other.”

Later Years

Roger Sherman worked hard to convince his fellow Connecticut citizens to ratify the Constitution, which its General Assembly did by a vote of 128 to 40 on January 19, 1788. Sherman was chosen as one of Connecticut’s representatives. When New Hampshire became the ninth State to ratify, the new United States Government was established and on March 4, 1789, government under the Constitution began operations. By May 29, 1790 Rhode Island became the last of the thirteen States to ratify. Sherman served the House well in various capacities until, on the resignation of Senator William Johnson he was elected in May 1791 to fill the unexpired Senate term, a seat he occupied until his death.

On April 15, 1793, the cornerstone of Union Hall, later known as “South College,” was laid on the Yale campus. Mayor Sherman was one of the dignitaries present. He was now an old man of 72, respected and honored by all his fellow citizens, venerated, and loved by his wife, ten living children and eleven grandchildren. His stalwart and active frame seemed still to promise years of usefulness. But his health suddenly failed; he was stricken with an attack of typhoid fever. For two months he lingered, but his dry humor did not desert him. When a consultation of physicians was deemed in order he was asked if he would object. “No,” was the reply, “I don’t object; only I have noticed that in such cases the patient generally dies.” On July 23, 1793 came the end. “He was” wrote Yale President Stiles, “an extraordinary man, a venerable uncorrupted Patriot.”18 Interment was in the cemetery on New Haven Green. When this cemetery was abandoned in 1821 Sherman’s remains were removed to Grove Street Cemetery, New Haven, where the weathered tablet covering his tomb may still be seen.

Author’s Note:

Roger Sherman, prominent signer of the Declaration of Independence and several other significant documents, was a Statesman and Founding Father during the formative period of our country. It is of some significance to me, William Eliot Boardman, proud member of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, that Roger Sherman was my great, great, great grandfather. It is also amusing (to some of us) to contemplate the following: if we apply the average human gestation period of 280 days, and some elementary arithmetic, to daughter Mehetabel’s 1/28/1774 birth date, we could conclude that, had the affairs of state and business preoccupied Roger more, or for that matter, had his wife Rebecca suffered from a headache, on or about April 24, 1773, your proud Descendent, as well as several hundred others, would not be here now to honor him.

I cannot claim credit for this work except as editor; most of it has been shamelessly extracted from the book Roger Sherman Signer and Statesman, written by my late uncle Roger Sherman Boardman. A review of this book is included as Appendix A. A much briefer biographical sketch, The Sherman Connection, written by my late brother-in-law Eric Marsden, a career journalist with the London Times, is included as appendix B. Eric had prepared this as part of a story about my family, but he died before it was published.

Sources:

- Adams, J. (1850). Works (ed. C.F. Adams)(10 vols.). Little, Brown.

- Boardman, R. S. (1938). Roger Sherman Signer and Statesman. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Brown, W. G. (1905). Oliver Ellsworth in the Continental Congress, American Historical Review, X. American Historical Review.

- Edwards, J. J. (1842). Works, vol. II. Andover, MA: Allen, Morill & Wardwell.

- Farrand, M. (1911). Records of the Federal Convention (3 vols.). Yale Univ. Press.

- Hart, A. (1926). Formation of the Union, 1750-1829 (Epochs of American History series). Longmans, Green & Company.

- Morgan, F. (1904). Connecticut as a Colony and as a State. Hartford: Publishing Society of Connecticut.

- Sanderson, J. (1911). Lives of the Signers. Farrand.

- Stiles, E. (1901). Literary Diary (ed. F.P.Dexter)(3 vols.) Scribners.

- Washington, G. Writings (ed. Sparks) IX.

- Wilson, W. (1902). A History of the American People, vol.II. Harper.

Appendix A

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography October 1938

BOOK REVIEWS

Roger Sherman Signer and Statesmen. By Roger Sherman Boardman.

(Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1938, xi, 396 p. Illustrated. $4.00)

The biography under review is a most thorough, scholarly, and well written piece of work. The importance of Roger Sherman in our early national life has not been fully appreciated. His contemporaries – Franklin, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison – were so great as to overshadow any lesser lights. Add to this Sherman’s innate modesty and it becomes easy to see why so little is known of the only man who signed the Association, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution (vide, p.122).

Three factors appear to have exerted a most profound influence upon Sherman’s life: his religion; his constant efforts to serve his state and nation; and his essentially legalistic attitude. He was always Judge Sherman: his reasoning was ever close and 1ogica1. However, he placed his duty to his fellow citizens on a higher plane, as he resigned his position on the bench of the Superior Court of Connecticut in order to assume the duties of a representative of his state in the first Congress of the United States.

Mr. Boardman tells the story of Sherman’s life against a background of the history of his time. From the quiet of a Massachusetts town in the period following Queen Anne’s War, the reader feels the increasing tempo of events as the break with England approaches. The stormy days of the American Revolution, followed by the rise of a new nation form the heroic setting for Sherman’s mature years. Few biographies within the reviewer’s experience so closely and so successfully identify the personal affairs of one man with the march of time. Not infrequently the importance of the man dwindles and is immersed in the sweep of events, but, after all, that is true to life.

A few items deserve particular attention. The facts connected with the history of the Susquehanna Company, and with Connecticut’s claim to land in the Wyoming valley are clearly stated. Sherman, in common with most citizens of his state, upheld its claims as opposed to those or Pennsylvania.

The decision of the Court of Commissioners at Trenton (1782) was unanimously in favor of the latter. The real significance of the Wyoming Controversy lies in two points, First, it may be regarded as one phase of the westward movement. Secondly, the decision of the Trenton tribunal was epoch-making in that it was the first case of a decision by arbitration of any controversy between two states of the United States” (p. 159).

Several appendices of great value bring this book to a close. Additional data on the Sherman almanacs is given In Appendix A. This includes a list of the several almanacs, together With their locations. The numerous, committees on which Sherman served are enumerated in Appendix C, while a most useful list of the Sherman letters quoted In the volume is given in Appendix D. Appendix E is devoted to a commendable Bibliography. An index brings the work to a conclusion,

No more significant biography of Roger Sherman has yet been written. In a very real sense, Mr. Boardman has made an excellent contribution to American biographical literature.

ALBAN W. HOOPES

Member American Philosophical Society

Appendix B

THE SHERMAN CONNECTION

By Eric Marsden

Roger Sherman was not only a signer of the Declaration of Independence – he was one of the inner group who helped Thomas Jefferson to draft it.

Roger Sherman was born on April 19, 1721, in Newton, Mass. He had little formal education and was largely self-taught. He was apprenticed to a shoemaker until he was 22, but studied law privately and became a successful advocate and was later appointed a state judge. He was a member of the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1791 and of the Senate from 1791 to 1793. In retirement he became mayor of New Haven.

Sherman holds a unique distinction in America’s constitutional history. He was the only person to have signed all four State papers which marked the creation of the U.S. Apart from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution he also signed the Articles of Association (1774) and the Articles of Confederation.

Sherman also played a key role in framing the Constitution by averting a dispute between the larger and smaller states of the proposed Union. In the Convention of 1787 the larger states backed Virginia’s contention that in a bicameral legislature “the rights of suffrage ought to be proportioned to the quotas of contributions, or to the number of free inhabitants.” If they were to bear the greater burden they demanded a bigger share of control. The smaller states stuck to their insistence on equal rights for all states.

The deadlock was broken by Sherman’s proposal that there should be one House with equal representation and a second with proportional representation. After amendments had been agreed relating to federal and state taxation this proposal, known as “the Connecticut compromise,” was accepted.

The Boardman family became linked to Roger Sherman through the marriage on May 2, 1861, of Dr. Samuel Ward Boardman to Sarah Elizabeth Greene, Sherman’s great-granddaughter.

Sarah Greene also had a formidable pedigree from her father, the Rev. David Greene, whose immigrant ancestor in 1649, Thomas Greene, was from Leicester, England. A genealogist, Lora S. La Mance, traced the Greene’s origins to Sir Henry Greene, a Yorkist who was beheaded on the order of Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV, in the Wars of the Roses. La Mance also claimed that the American family had royal links with the Stuart line in Scotland, and was lineally descended from the uncle of William the Conqueror. “We have five saints in our direct lineage and a dozen Crusaders.”

Sarah Greene was undoubtedly a remarkable woman in her own right. She helped transform the life and fortunes of Dr. Samuel Ward Boardman, who had had a troubled start to his career and whose first wife had died young. He and Sarah were married for more than 50 years and had nine children, and he attained eminence as an educator and author.