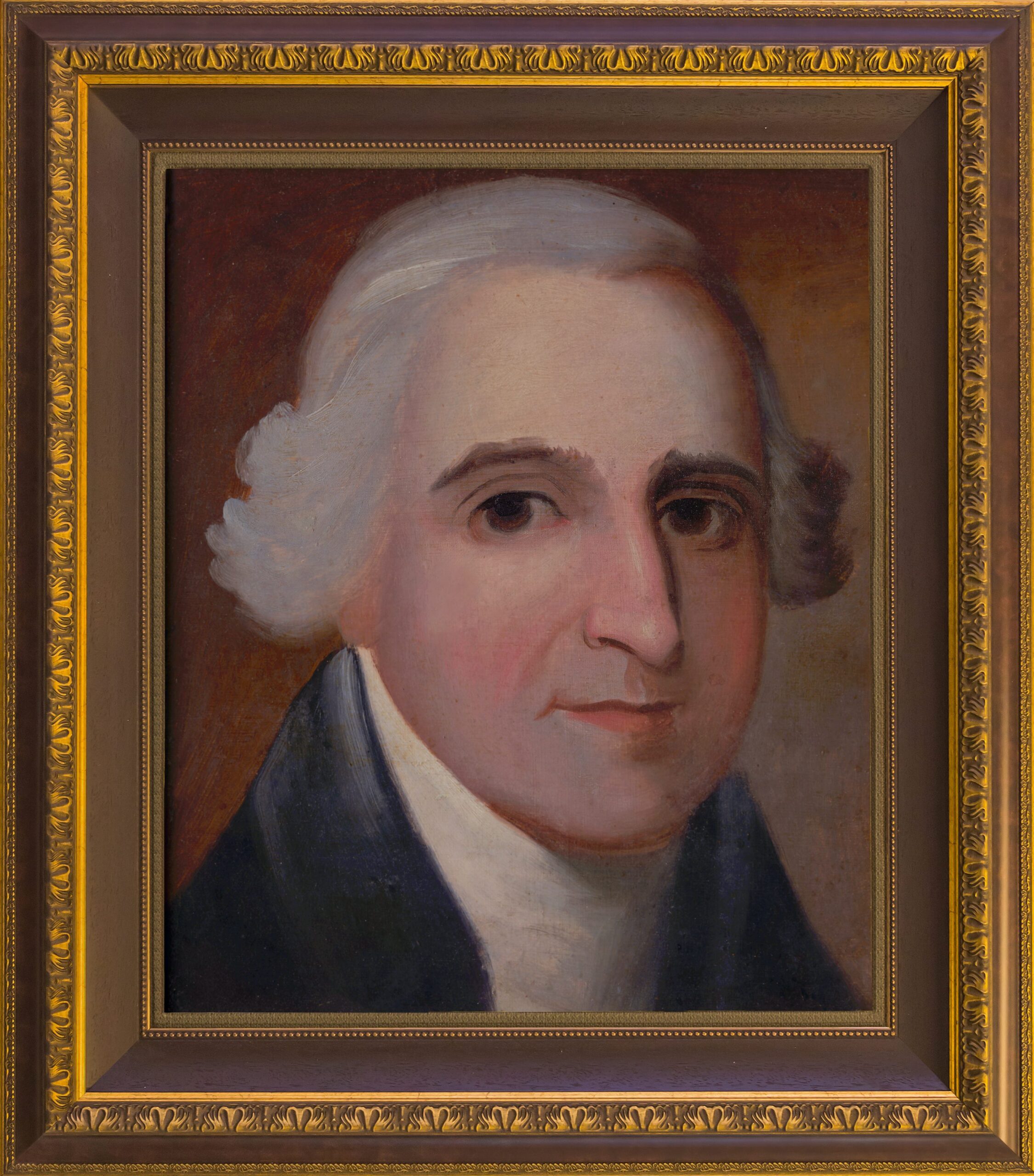

Title: Portraits of signers of the Declaration of Independence

Call Number: MSS 12130

Citation: Robert Edge Pine. Copies of Pine's Portraits of Signers of the Declaration of Independence,1820, Accession #12130, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

This photo has been identified as being free of known restrictions under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights.

Spouse Information:

Ann Bourne

Button Gwinnett

Button Gwinnett was born in 1732 in Gloucestershire, England, one of seven children of the Rev. Samuel and Anne Eames Gwinnett. The Gwinnett name was originally Gwynedd, a name of long standing from the northern part of Wales. His mother, Anne Eames, had prominent relatives in Herefordshire.

Not much is known of his formal education, but he was apprenticed to a merchant in the city of Bristol. There he married and became an exporter of goods from Bristol to America before 1760. He was the sole owner of the Brig “Nancy”, but his mercantile business proved unsuccessful. When he became indebted locally his ship was seized and sold to pay his debts.

Allured by the promise of better days ahead in the colonies, he and his family sailed to Charleston in 1765, and he established himself as a trader there for a few years. Later he sold all his merchandise and moved to Savannah. Then he purchased the island called St. Catherine’s, a tract of land of 36 square miles off the coast of Georgia near the flourishing port of Sunbury, and became a planter. In this endeavor he became acquainted with a group of settlers who had come from New England to Sunbury. One of them was Lyman Hall, a future signer of the Declaration, who had re-settled there from Fairfield, Connecticut.

Through this friendship with Hall, Gwinnett developed an interest in politics. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace in 1767-8, and in the next year he became a member of the Georgia Colonial Assembly. During the next five years financial or other problems seem to have prevented further involvement in public service. He acquired property in St. John’s Parish in 1772 but in the following year, creditors seized his properties. However, he was allowed to continue living in his home there for the rest of his life.

Mr. Gwinnett had from his earliest emigration to America taken a deep interest in the welfare of the colonies; but, from the commencement of the controversy with Great Britain, he had doubts that the cause of the colonies could succeed. In a letter to Roger Sherman, Lyman Hall wrote that he regarded Gwinnett at that time as a “Whig to excess.” To Button, successful resistance to so mighty a power as that of the United Kingdoms appeared extremely doubtful. This continued to be his concern until about the year 1775, when Lyman Hall helped persuade him to change his views. This change in his sentiments produced a corresponding change in his conduct. He now came forth as an open advocate of strong and decided measures in favor of obtaining redress, if possible, of American grievances, and of establishing the rights of the colonies on a firm and enduring basis.

In the early part of the year 1776, he was elected by the General Assembly in Savannah, and to be a representative of the province of Georgia, in the Continental Congress. Agreeable to his appointment, he journeyed to Philadelphia and in the following month of May took his seat in the national council. While he is not known as a major player in the debates, John Adams noted that “Hall and Gwinnett are both intelligent and spirited men, who made a powerful addition to our Phalanx.” Gwinnett voted for independence on July 2, for the declaration on July 4, and signed his name to the parchment of the Declaration of Independence on August 2. He returned to Savannah at the end of that month.

Gwinnett’s ambition was to become a general of Georgia troops, but the man who would become his nemesis, Lachlan McIntosh, an experienced officer who in 1776 had repulsed the British assault at the Battle of the Rice Boats in the Savannah River, was appointed instead. He was commissioned a Brigadier General in the Continental Army and charged with the defense of Georgia’s southern flank from British attacks from Florida. This incident was the beginning of a bitter quarrel between the two men that would ultimately lead to Gwinnett’s death.

Failing in his military endeavors, Gwinnett ran for and was elected Speaker of the Georgia Assembly in October, 1776, and was then re-elected to the Continental Congress. In the following months, he played an important role in drafting the first constitution for Georgia, and in preventing Georgia from being absorbed into South Carolina.

When the President of the Georgia Assembly, Archibald Bulloch, died on March 4, 1777, Gwinnett was immediately elevated to fill his position, effectively becoming Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Army. This achievement was a great honor for Gwinnett, and demonstrated that he was held in high public esteem for his ability and integrity.

On that same day he was directed by the Council of Safety to draft militia and volunteers for a campaign against the British in east Florida, the objective being to cut off supplies to their stronghold at St. Augustine. He was also informed, by letter from John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress then in session in Baltimore, about treasonable acts by George McIntosh, a member of the Georgia Assembly and a brother of General Lachlan McIntosh. Gwinnett ordered General McIntosh to arrest his own brother and place him in irons, and ordered McIntosh to lead what turned out to be a poorly planned and poorly led military expedition. Both Gwinnett and McIntosh publicly blamed each other for the failure of the campaign further straining their relationship.

Both McIntosh brothers were furious at and envious of the new governor. Gwinnett was exonerated from fault in the failed expedition by an inquest, but lost his bid for re-election as Governor. On May 1, 1777, Lachlan McIntosh addressed the Georgia assembly denouncing Gwinnett in the harshest of terms, proclaiming him “a scoundrel and a lying rascal”. Gwinnett called on McIntosh and demanded an apology or satisfaction, and when McIntosh refused Gwinnett challenged him to a duel.

On May 16, 1777, a pistol duel took place in Sir James Wright’s pasture a few miles east of Savannah. The engagement took place with only 12 feet separating the antagonists. Both men were wounded, but Gwinnett died within a few days of a gangrene infection from his wound on May 27, 1777. He might well have said, as did the lamented Alexander Hamilton when fatally wounded in his duel with Aaron Burr:” I have lived like a man, but have died like a fool”.

McIntosh was charged with murder but he was acquitted in the ensuing trial. Fearing Gwinnett’s allies would take revenge on McIntosh, George Washington ordered him to report to Continental Army headquarters on October 10, and he spent the winter at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

Thus, fell Button Gwinnett, one of the patriots of the revolution. Though entitled to the gratitude of his country for the services which he rendered her, her citizens will ever lament that he fell victim to a false ambition, and to a false sense of honor.

In appearance, Mr. Gwinnett was tall and with a noble and commanding appearance. In his temper he was irritable, yet in his language he was mild. In his manners he was polite and graceful. Happy would it have been for him had his ambition been tempered with more prudence; and happy for his country had his political career not been terminated in the prime of life.

Button Gwinnett married Ann Bourne in Staffordshire, England, on April 19, 1757. She was the daughter of Aaron Bourne, a Wolverhampton grocer. They had 4 children, all daughters, three of whose births were recorded in the Collegiate Church in Wolverton. Three of his daughters died young without issue. The fourth, Elizabeth Ann (Betsy) Gwinnett, was baptized January 4, 1762 and died about 1786. She married Peter Belin on March 26, 1779, but there was no surviving issue.

The name and memory of Button Gwinnett live on in many ways, such as in Gwinnett County, GA, named for him; in the Button Gwinnett District of the Boy Scouts of America in Atlanta; in the Button Gwinnett Elementary School in Hinesville, GA; in the Button Gwinnett Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, Lawrenceville, GA; et al.

The State of Georgia built a large memorial in its capital city in 1848, Augusta, to the memory of the three Signers from Georgia; and, in 1955 his bust was one of the first three placed in the Georgia Hall of Fame, the accompanying busts being those of Georgia’s two other signers.

A monument in Savannah’s downtown Cemetery in Colonial Park marks the site of Gwinnett’s grave, though the exact location is not known because the tombstone was lost when Union cavalry camped there in the Civil War and vandalized or destroyed many grave markers.

This patriot died leaving an insolvent estate; but his signature today is very rare among the Signers. Collectors have paid many thousands of dollars to own it!

Edited for DSDI by member Rieman McNamara, Jr., 2007

Sources:

- The Signers of the Declaration of Independence, A Biographical and Genealogical Reference, by Della Gray Barthelmas, McFarland & Co.

- Lives of the Signers of the Declaration, by B. J. Lossing, a reprint of the 1848 edition of Geo F. Cooledge & Bro.

- Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, by the Rev Charles A. Goodrich,William Reed & Co,1856 (Colonial Hall)

- James Edward Oglelthorpe, The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- The Augusta Chronicle.

- Georgia Historical Society.

- Rieman McNamara, Jr., DSDI member

- Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence,Volume 7,The Rev. Frederick Wallace Pyne, Picton Press, Rockport, Maine, 2000

- Lachlan McIntosh and the Politics of Revolutionary Georgia, Harvey Jackson, 1979